Everywhere you look right now, from Honda to BSA, Triumph to Yamaha, it feels like the motorcycle industry has one word on its mind: nostalgia. Retro tanks. Round headlights. Vintage badges. But here’s the question: are brands selling us heritage because we love it… or because consumers can’t afford to move forward?

Walking around the stands at EICMA, it was hard not to notice what’s happening. From the Honda CB1000F, the BSA Bantam 350, Triumph’s Speed Four, Kawasaki’s Z-900RS, and even Yamaha’s XSR lineup, there has been a significant shift towards vintage motorcycle models.

Manufacturers are reaching back to the past for inspiration. However, when nearly every major manufacturer starts reviving names from the 1960s and 1970s, it usually means one of two things: either we’re in a golden age of motorcycle culture, or the industry is tightening its belt and playing it safe.

Watch the full video below:

The Rise of Retro

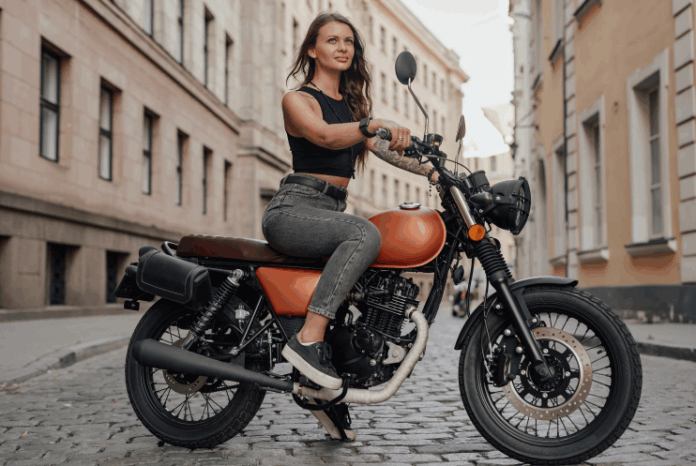

Let’s start with the obvious: nostalgia is a powerful selling point. For a bike, his machine isn’t just a means of transport; it’s an emotion on wheels.

When the world feels uncertain, whether it’s inflation, war, or post-pandemic burnout, people crave something familiar. They want a sense of stability. Something that feels like “home.”

That’s why you’re seeing retro models dominate press releases in 2025. They’re comforting. They whisper simplicity in an era of touchscreen, dashboards and subscription software.

However, there’s also a business reason behind this throwback fever. Retro bikes are generally less expensive to develop and produce. Think about it: you can use an existing platform, give it a classic tank and a round headlight, and boom, a “new model”.

And not just any new model; it taps into emotion instead of relying on R&D. That’s not me being cynical. That’s strategy. When economies slow down, companies tend to be more cautious. They lean on heritage because heritage already sells itself.

The Economic Reality

Are we actually in a recession? Well, globally, we’re hovering close. We’ve witnessed inflation eroding disposable income, interest rates have surged, and luxury spending has shifted from designer cars to handbag trinkets like those from Labubu. Motorcycles have fallen to the same fate as other luxury items.

In simple terms, fewer people are buying brand-new high-end bikes, and manufacturers know it. So how do the manufacturers respond?

They pivot. They shift focus toward attainable emotion. That’s why we see affordable 350s, 400s, and 500s on nearly every stand regardless of the company. Manufacturers have realised something fundamental: in uncertain economies, volume saves brands. It’s no longer about selling one single superbike for £20,000; it’s about selling twenty smaller bikes for £5,000. And well, Retro styling makes that easy. You’re not selling horsepower anymore, you’re selling an emotion.

The Emotional Sell

Let’s be real here, we know motorcycles are already irrational purchases. They’re expensive, they’re dangerous and compared to a car or a van, they’re not practical. Realistically, nobody needs one.

We buy motorbikes because they evoke emotions in us. And right now, nostalgia is one of the strongest emotions in the world. People don’t just want speed; they want stories. They want bikes that remind them of their dad’s garage, that old smell of petrol and metal polish, and a simpler time before the world started measuring everything in data and carbon credits.

Manufacturers know that. So they build machines that make us feel like we’re part of that legacy, even if the bike just rolled off a factory floor in India, Thailand, or China. That’s not manipulation. That’s emotional design. It’s marketing in its most human form.

What It Means for the Industry

Is this wave of nostalgia a bad thing? Not necessarily. It’s currently keeping the motorcycle world alive during an economic downturn. Entry-level retros attract new riders, expanding a shrinking market. Retro machines are cost-effective and easier to insure; they remind older riders why they started riding in the first place.

As a consequence, nostalgia serves as both a survival strategy and a revival strategy. However, as with anything, there is a risk.

If every company is busy looking backwards, who’s building the next chapter? Innovation doesn’t stop because times are hard, but it does hide for a while. But when the economy recovers, the brands that took risks during the tough years will lead the next revolution. So yes, nostalgia keeps the lights on. But evolution keeps the fire burning.

So, in conclusion, is it the case that manufacturers are selling nostalgia? Yes. Absolutely. But is that a bad thing? Not at all.

It’s merely a symptom of the cautious and cost-saving times we’re living through. But truthfully, that’s okay! Because sometimes, just sometimes, when the world feels uncertain, it’s good to be reminded where we came from, as long as we don’t forget where we’re going.

I’m Saffy Sprocket, reporting from Milan. For more EICMA news, deep dives, and two-wheeled stories, hit that subscribe button and keep those sprockets spinning. Ride safe, stay crazy, and I’ll see you on the next adventure.